by Neon

Among the many influences that shaped the early “Oriental

fantasy” and early “belly dance”

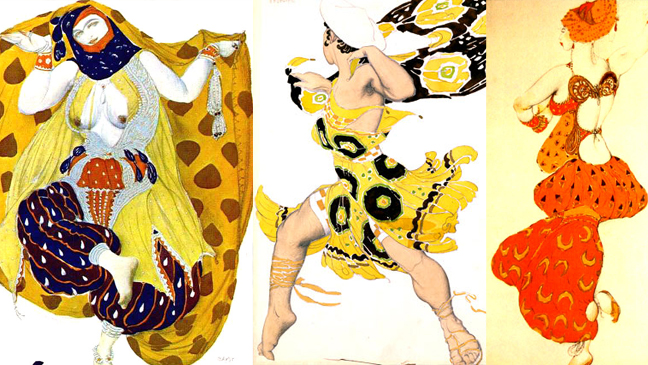

look are the exotic costume designs done for the “Ballets

Russes” by Art Nouveau designer and illustrator

Leon Bakst.

His lavish, flamboyant, colorful costumes for “Scheherezade”

(Paris, 1910), "Cléopâtre"

(1910), “L'Apres-midi d'un Faune” (1912)

"Le Dieu Bleu," "Thamar," "Polovets

Dances" established the image of the Ballets

Russes, caused a sensation in the world of European

fashion and interior decoration, and had a direct

impact on the “odalisque,” “Salome”

and other early 20th-century dance costume themes.

Unlike classsical ballet costumes, Bakst’s costumes

freed the torso. The costumes were supported only

by the bra and hip belts.

Bakst’s Orientalist designs inspired Paul Poiret

who admired his work. Trend-setting fashion designer

of that era, Poiret introduced the “Directoire”

tube-like dresses and encouraged women to switch from

the corset to the bra. In 1913, as a tribute to the

Ballets Russes, Poiret produced bold-color heavily-beaded

and appliqueed fashion designs featuring harem pants,

“lampshade” tunic, "minaret"

skirts, turbans, exotic jewelled slippers and "barbaric"

(what we today call “tribal”) jewelry.

Even the "shocking" introduction of the

V-neck for day wear echoed the Orientalist trend.

Aigrettes replaced tiaras. Bakst designed Orientalist

fabrics for Poiret, dressing the European elite in

canary yellow, bright blue, jade, cyclamen, and henna.

Leon Bakst (1866-1924) was born to a Jewish family

in Grodno, Belarus, and studied at the Academy of

Fine Arts in St.Petersburg, Russia. He started his

artistic career as an illustrator for magazines and

soon expanded to stage and costume design. In 1909

he began his collaboration with Diaghilev, Russian

theater entrepreneur and founder of the Ballets Russes,

where Bakst became the artistic director. In 1912,

Bakst had to leave St. Petersburg (being Jewish, in

an era of state Christianity, he was not allowed to

reside in major Russian cities) and settled in Paris.

Bakst was fascinated with both dance and Orientalism.

His portrait of Isadora Duncan dating from her Russian

tour in 1908 reveals his interest in sensuality expressed

in movement.

Bakst traveled to North Africa

and studied in Paris with the French Orientalist painter

Jean-Leon Gerome. Bakst’s costume designs incorporated

motifs from Arabia, Turkey, Central Asia and the Caucasus,

as well as design elements from Persian miniatures,

Greek vase paintings , the art of Byzantium and ancient

Egypt.

Bakst's Oriental/exotic designs developed along the

lines of costuming similar to what we see in our modern

belly dance world -- the sleek and "nude"

"diva/seductress" style ("cabaret”)

and the colorful “folkloric,” “character”

style (“tribal”).

“Ballets Russes" had

tremendous impact not only on European fashion and

Oriental dance costume, but also on the movement vocabulary

of "belly dance." Along with the original

Michael Fokine’s fantasy choreographies of the

Ballets Russes the Western dance world absorbed many

elements of Caucasian female folk dances - ethereal

gliding walks on releve, powerful lift in the upper

body, expansive arm patterns, streaming, floating

veils. The veil dance from “Cléopâtre”

was one of the first uses of the veil to convey Orientalist

flavor.

Another interesting digression from classical ballet

standards was the determination of Michael Fokine,

choreographer of Ballets Russes, to give the lead

role in Cléopâtre and other ballets "to

a dramatic actress rather than to a ballet dancer."

The Orientalist fantasy aesthetics of Ballets Russes

shifted the emphasis from dance technique to the impact

produced by acting and exotic look.

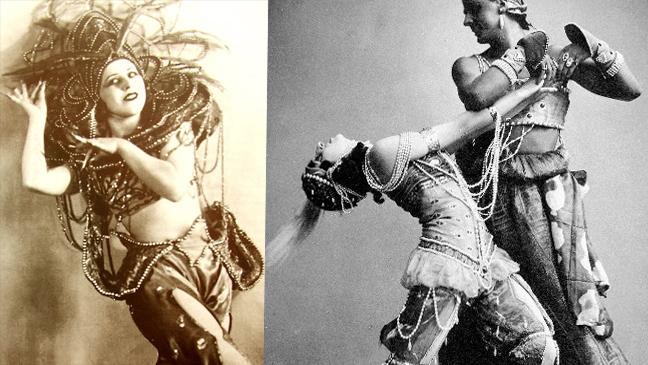

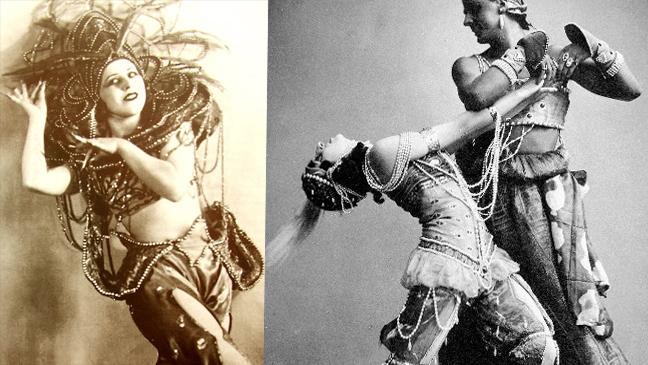

The star of “Cléopâtre,”

Ida Rubinstein, was not a trained ballet dancer; she

took private lessons from Fokin in 1907-08 and starred

in Cléopâtre in 1910. Michael Fokine

wrote about training her to dance in Salome: "I

had to teach Rubinstein simultaneously the art of

the dance and to create for her the Dance of Salome.

Before this, she had studied very little, and showed

very little progress in it. Her energy and endurance

were of great assistance, as was her appearance...She

was tall, thin and beautiful."

The demand for sensual, exotic goddess-like stage

persona was so imperative, and the reliance on the

the power of design and costuming was so strong in

Ballets Russes, that Fokine choreographed Ida Rubinstein's

numbers to reveal her beauty without making her actually

*dance.* Bakst helped Fokine to convince Diaghilev

to let Ida become the star of his productions.

The American tour of Ballets Russes “Cléopâtre,” “Thamar,” and “Scheherazade” resulted in a flurry of the early Hollywood Orientalist films (e.g. "Thief of Bagdad," 1924) imitating Bakst’s costumes, set designs, and the Romantic portrayal of the remote and wild Orient by Ballet Russes -- sealing the iconography of eroticism and exoticism of the Western perception of Oriental dance.